This little essay is a commentary on the recent paper by my colleagues Nicolas Baumard and Jean-Baptiste André, ‘The ecological approach to culture‘.

[Homo sapiens] is as much a rule-following animal as a purpose-seeking one

(Hayek, 1973, p. 11)

‘Culture’ is more than dollar bills on the sidewalk that you can pick up if you want

Baumard and André’s ecological approach to culture (Baumard & André, 2025; henceforth B&A) is a welcome framework for a number of reasons. It parsimoniously places culture within the more general framework of eco-evolutionary processes. Critically, it uses the notion of ecological legacy to integrate the goal-directed nature of human action (people execute adaptations designed to maximize their inclusive fitness) with the obvious fact that a human mind is not starting from nowhere: it comes into a community where there are already artifacts, institutions, conventions, and words. B&A shifts the lens from viewing people as passive culture-takers (culture is out there; people soak it up as passively as they inherit genetic mutations) to active, strategic culture-makers (cultural traditions are an available part of the environment, that agents can make use of or reshape depending on their strategic interests). It has the potential to integrate the study of culture more closely with evolutionary biology, with cognitive science, and with the rational actor tradition of economics and political science.

But – there is always a ‘but’ in a commentary – as currently articulated, the ecological approach omits or under-acknowledges one the most important aspects of culture: its normative force. Cultural patterns – norms, social roles, standards of good taste, customs – are not just things one can do, but things one feels one should do, perhaps even one has to do. Culture is, to quote Ward Goodenough, ‘whatever it is one needs to know or believe in order to operate in a manner acceptable to [the society’s] members’ (cited in Keesing, 1974, p. 77). Evolutionary anthropologists have focused on the wonderful practical consequences of culture, allowing humans to develop complex technologies and useful institutions at a speed way greater than that of genetic evolution. But let us not forget that culture is one of the main ways by which humans make each other miserable: it is normative culture that has consigned a good number of the humans that have ever lived to subordinate social roles, lesser shares of the common weal, oppressive gender or class expectations, secrecy about who they love, tedium, or even painful mutilation. Why? Why do people they feel they have to put up with all this, if they have evolved to maximize their inclusive fitness?For the most part, B&A is rather voluntaristic about cultural patterns. Cultural patterns constitute an available resource for us to use if it suits our inclusive fitness, and ignore if not. People ‘negotiate social norms to suit their goals or solve local problems’ (p. 2), and participate in conventions ‘when doing so aligns with their own adaptive interests’ (p. 11). People are like elephants in an environment containing paths previously made by other elephants: ‘they have the option of ignoring them….if they choose to use [them], it’s because they have advantages’ (p. 2).

Culture does not feel like this, something that is available to us if we find it useful, but that we have the option of ignoring. One of the central themes of social theory is quiescence: the very general tendency of humans to feel they have to go along with social orders, even ones that do not make a lot of sense, or seem to go against their interests. This puzzle was perhaps first articulated by Boetius, in his Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, published in 1577, but it echoes through Marx, Gramsci, Hayek, Bourdieu, Giddens, to Stuart Hall. B&A do go some way towards what is needed: they concede that, although cultural behaviors will usually be adaptive as long as individuals are free to choose what they do, individuals are not always free to choose. Sometimes they have been coerced or manipulated (p. 16). The authors also recognize, rightly, that the interests of different members of society are not generally aligned, and that this goes a long way to explaining the kinds of structures that persist.

However, the dichotomy ‘either people choose freely and then they do things in their inclusive fitness interests’, or ‘they are coerced and then they do things in the inclusive fitness interests of those coercing them’ is much too sharp. Cultural patterns lie somewhere in the middle. No-one is holding a gun to our heads to make us cut the camembert in the right way; but on the other hand, we depart from good manners at our peril. We have a ‘sense of should’ (Theriault et al., 2021): the prospect of violating cultural expectations, whilst sometimes attractive, is deeply stressful. We have to weigh the cost of non-conformity in any decisions we make, and sometimes that weight is heavy indeed.

We don’t want to drown the inclusive-fitness maximizing baby in the bathwater of quiescence. B&A’s position is attractive and must at some level be right. But it needs to be enriched with a stronger, inclusive-fitness compatible account of normativity, and of quiescence. In the remainder of this commentary, I will very briefly discuss some of the elements that might help us achieve this (for a fuller discussion, see Nettle & Heintz 2025).

The origins of normativity and quiescence

For normativity and quiescence to occur, there need to be adaptations in the observer, and adaptations in the actor. Of course, observers and actors are the same people – all humans are both – but this is a useful way of parsing the problem.

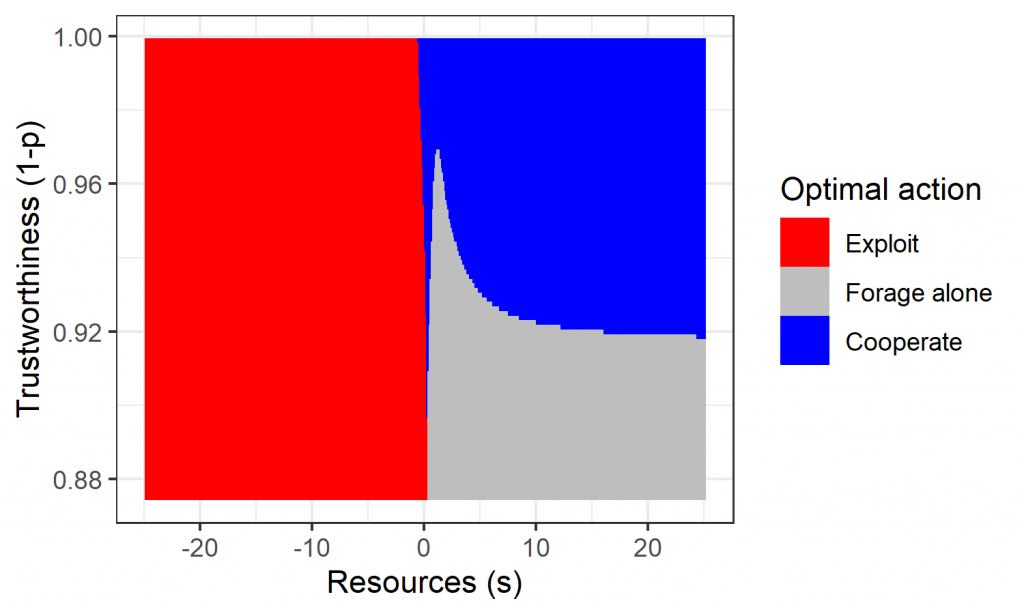

The observer belongs to a species that is highly collaborative. Humans make their livings by taking on many win-win social ventures with others, from raising a child together to building a salmon weir. But they have some decision latitude about which of these ventures to invest in, with which partners, and to what extent. Something we all need to be able to do, then, is evaluate a potential joint-venture partner. Are they cooperative? Will they assign proper weight to my interests? Do they value the same things in the outcome as I do? And, more simply, will it be easy to coordinate with them? For this reason, humans have evolved extensive abilities to store and update evaluations of others, evaluations that they use to choose who to work with, who to fight alongside, who to be friends with, and so on.

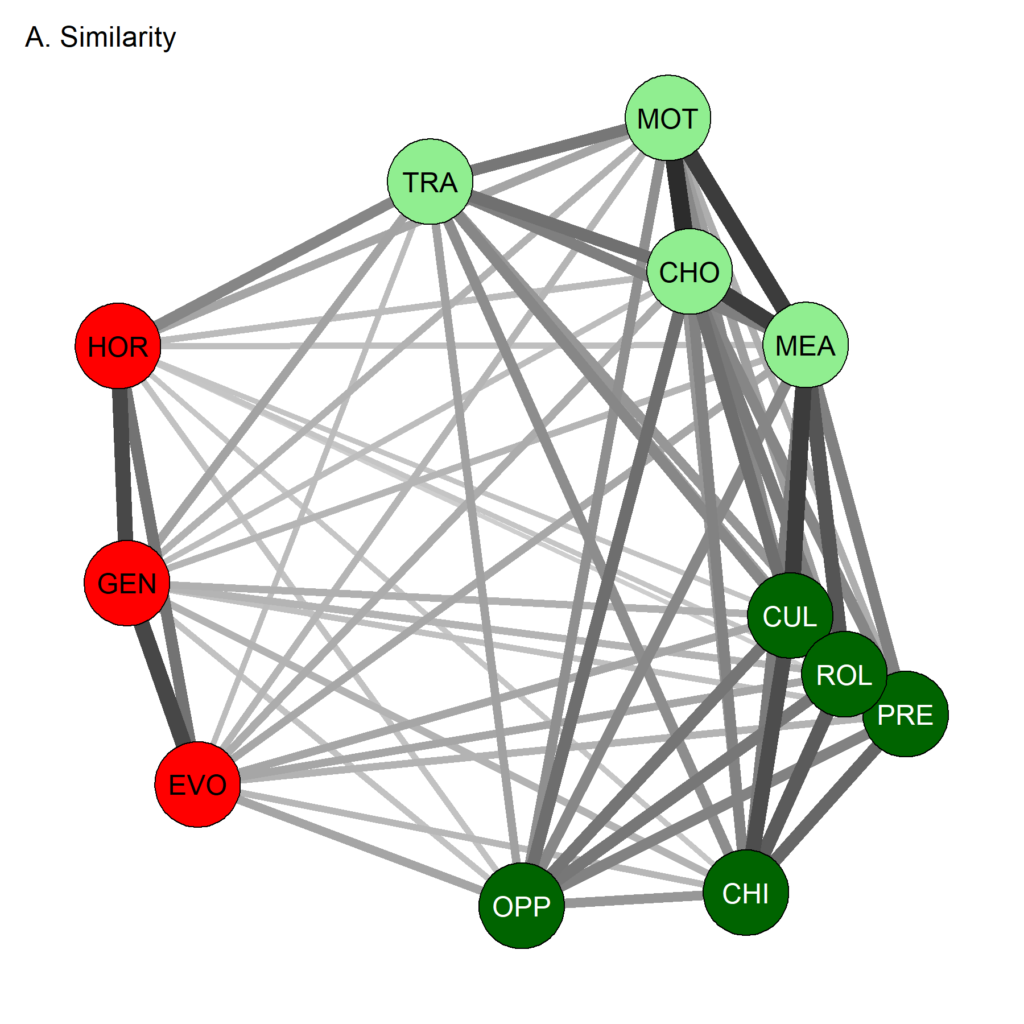

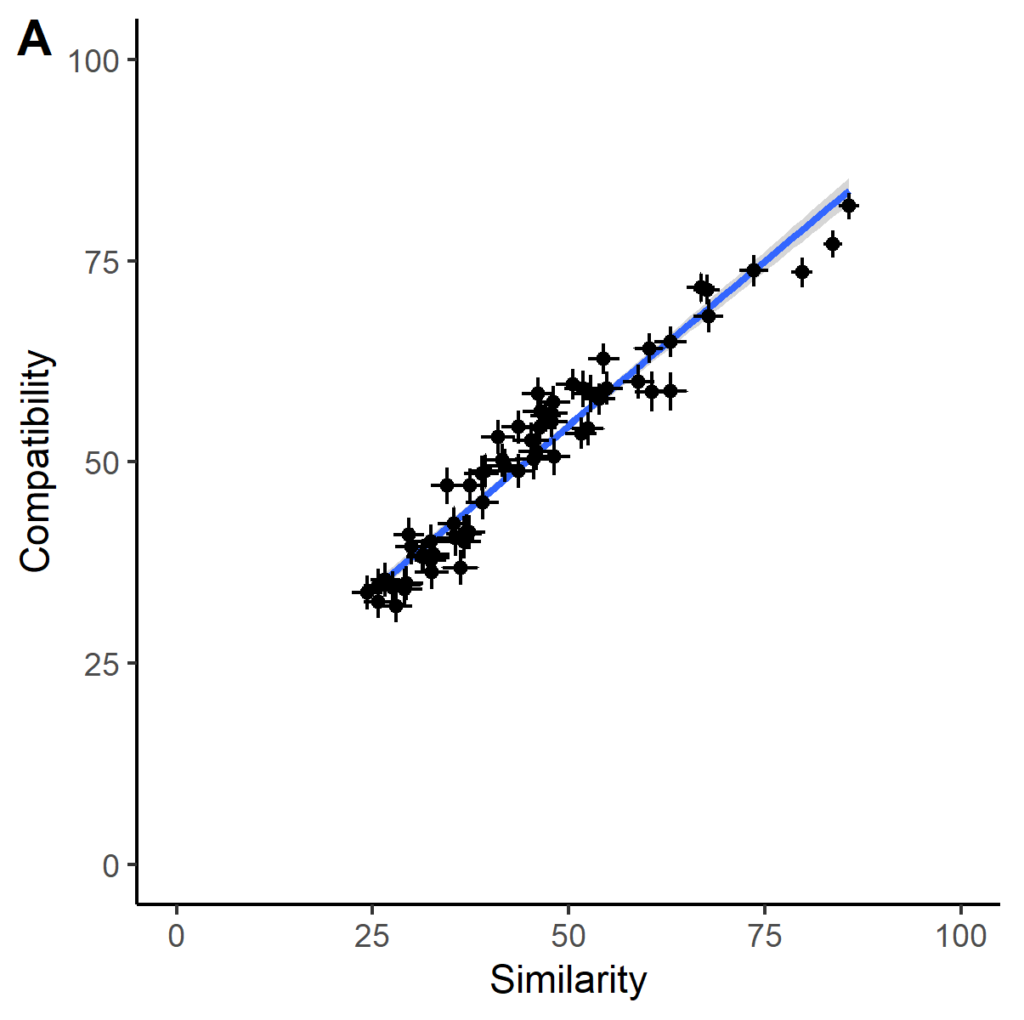

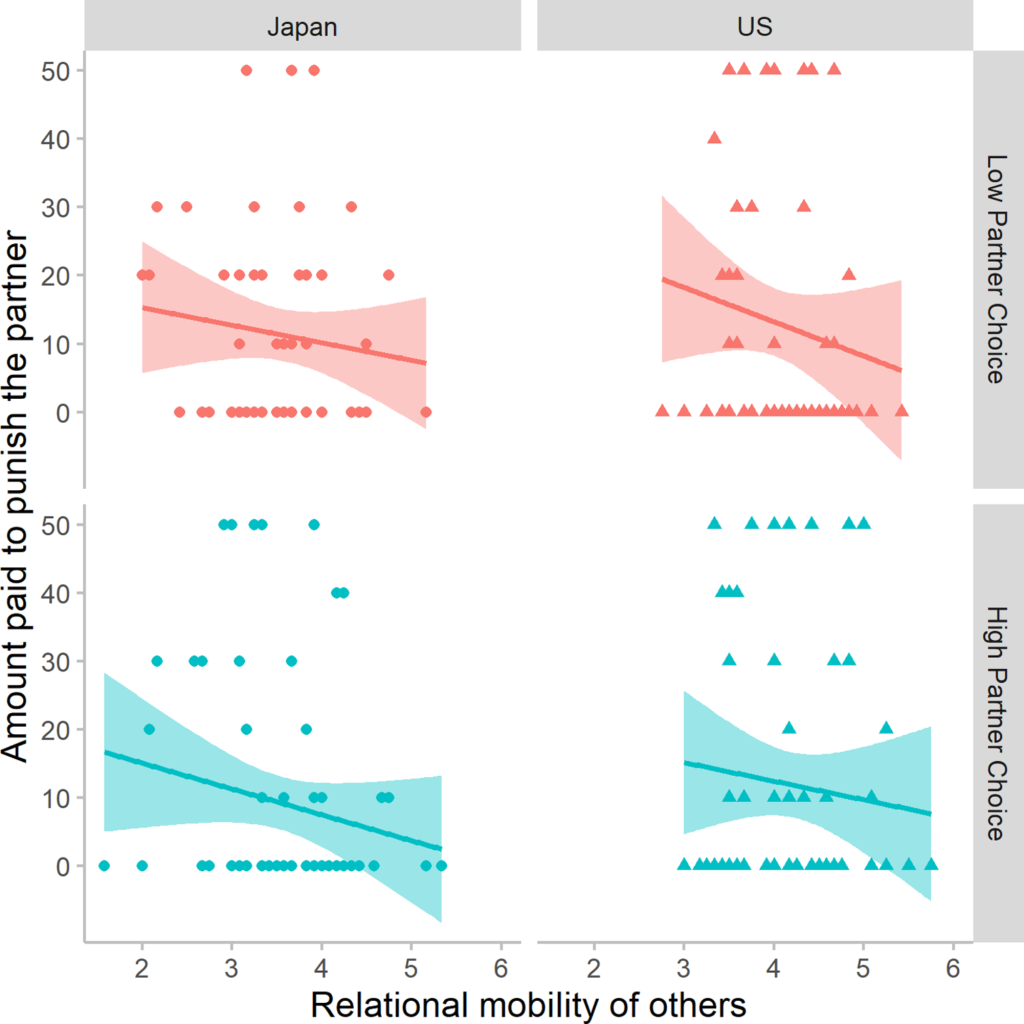

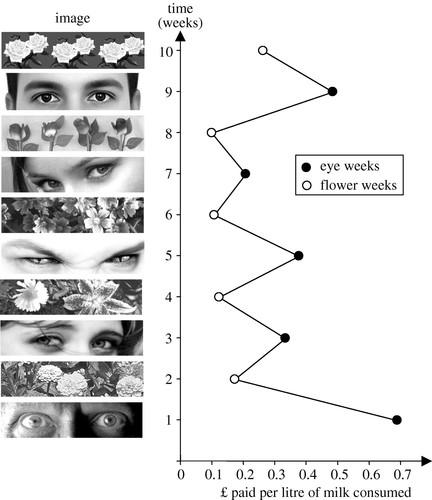

So far so uncontentious. It is clear why these evaluations would be sensitive to classic moral qualities, or to evidence of the weight the other person assigns to our interests, as evolutionary psychologists have documented. But normative cultural expectations come to be attached to all kinds of subtler things: the ways people dress, the way they part their hair, their manner of walking down the street. Why would these matter? Briefly, I would argue that a lot of what we want from collaboration partners is predictability. I don’t want to find myself halfway into a high-stakes collaboration with someone who turns out to have different valuations of outcomes, different understandings of the goal, or whose actions constantly cause me metabolically costly and perhaps disastrous prediction error. I have to infer their suitability as a partner from very minimal evidence prior to embarking on the joint venture. One thing I can see is how well they conform to my statistical expectations about behaviour in general, including in innocuous domains. The individual who, in the minutiae of interaction, causes me the least surprisal, is, other things equal, the one with whom joint-venture coordination is probably going to go the most smoothly. This means, other considerations equal, I am going to more positively evaluate someone whose behaviour is more similar to what I expected, even in domains that have no direct impact on my interests.

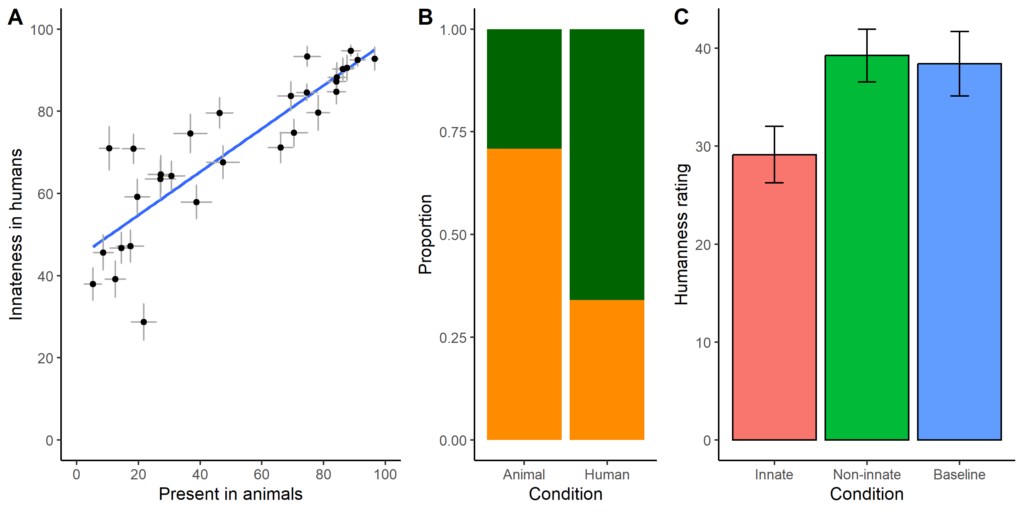

The actor, for their part, lives in a world where the evaluations in the minds of others in the surrounding community is a fitness-limiting resource. A human with no social partners is a dead human. Another way of putting this is that one of the inclusive-fitness goals of humans is to maintain positive evaluations in the minds of (the relevant) others. They must achieve this without knowing in detail what each of those others values. This means, minimally, that actors: (a) store and update representations of what others expect, both specific others and community members in general; and (b) they must have an else-equal preference not to violate those expectations. Keeping others’ evaluations as positive as possible is not always achieved by conformity: sometimes one might garner positive evaluations by performing an unexpected act of defiance. But, more often than not, the easiest way of maintaining positive evaluations with as much of the community as possible is by not violating expectations, certainly not violating them needlessly: the status quo is a safe default (Theriault et al., 2021). One definition of cultural knowledge is that is the actor’s theory of what other community members expect, a theory to which the actor can refer in navigating social life smoothly and competently (Keesing, 1974). Just knowing that something is a rule motivates people to follow it, even when it is arbitrary and at cost to themselves, and especially so if they believe that many others expect them to follow it (Gächter et al., 2025).

If we accept that people are motivated not to disappoint the expectations of others, are we back to cultural dupes, passive culture-takers? No. Maintaining normative compliance is one goal that humans have evolved to pursue, exactly because individuals who did so tended to have better social opportunities. But it is not the only goal, or even always the strongest. Just as people have to weigh the competing goals of sleeping and gaining resources, gaining status and caring for kin, they have to weigh the goal of maintaining positive social evaluations against other equally consequential goals. Existing work on norm psychology has correctly stressed our sensitivity to normative expectations, but perhaps gone too far in forgetting all the other countervailing goals people have too, that sometimes win out. B&A’s position, enriched as I sketch here, can function as a corrective. Evolutionary decision theory needs to incorporate not disappointing the expectations of others as one input into the calculus of decisions, albeit not the only or always the strongest one (for one discussion of how normative motivations may be integrated with others, see Gintis, 2016). Note that normative motivation is not the same thing as prosocial preference; one can harm someone or even many people by sticking rigidly to a norm). Other people’s expectations are an important constituent of the human ecological legacy everywhere, a source of potential danger if violated and benefit if met.

Explaining social change

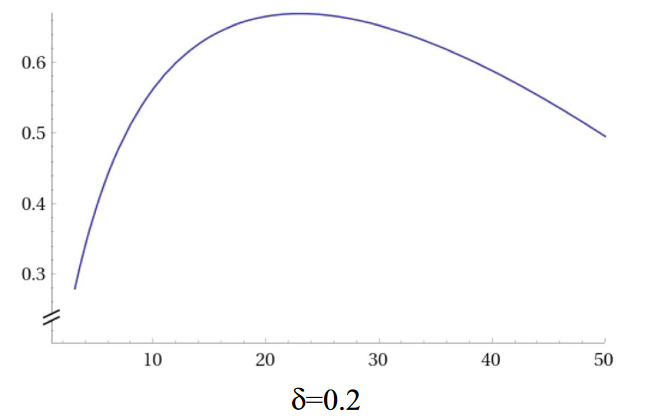

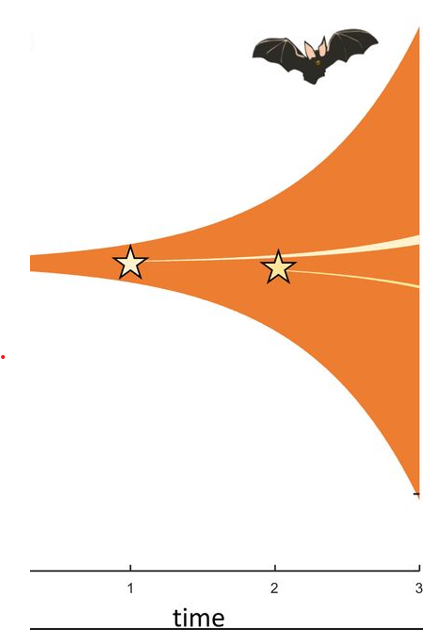

A strength of B&A’s proposal, compared to other evolutionary treatments of culture, is that it provides a stronger and clearer account of cultural change. Cultural change generally arises (among other reasons) when enough people find something that seems to them to be a better way of satisfying their goals (Singh, 2022). The normative refinement I have provided here tempers this slightly. Cultural change will arise when enough people find something that seems to them to be a better way of doing things, it seems better by a sufficient margin to overcome the aversion to violating normative expectations, and they manage to survive the social upheaval of getting there. (Equivalently, not violating expectations is, itself, one of the goals, and it has to lose out in order for change to ensue). At the cognitive level, people will prefer the new A’ to the established A not when the expected directed payoff of A’ seems greater than that of A, but when the expected value of A’ minus the terrible uncertainty and potential cost of violating expectation seems greater than the payoff of A (Theriault et al., 2021). This is a much stricter condition, which explains the ubiquity of quiescence, even in the face of disadvantageous conventions (see also O’Connor, 2019). At the behavioral level, the status quo will have a tendency to persist until things get really bad for enough people. In many cases, if the payoff surface is sufficiently flat, status quos can persist indefinitely without really being anyone’s optimum outcome, just because of the aversion to and uncertainty of violating mutual expectation. Indeed, in the limit, cultural patterns can persist that almost no-one values any more, simply because everyone believes that everyone else expects that they will continue.

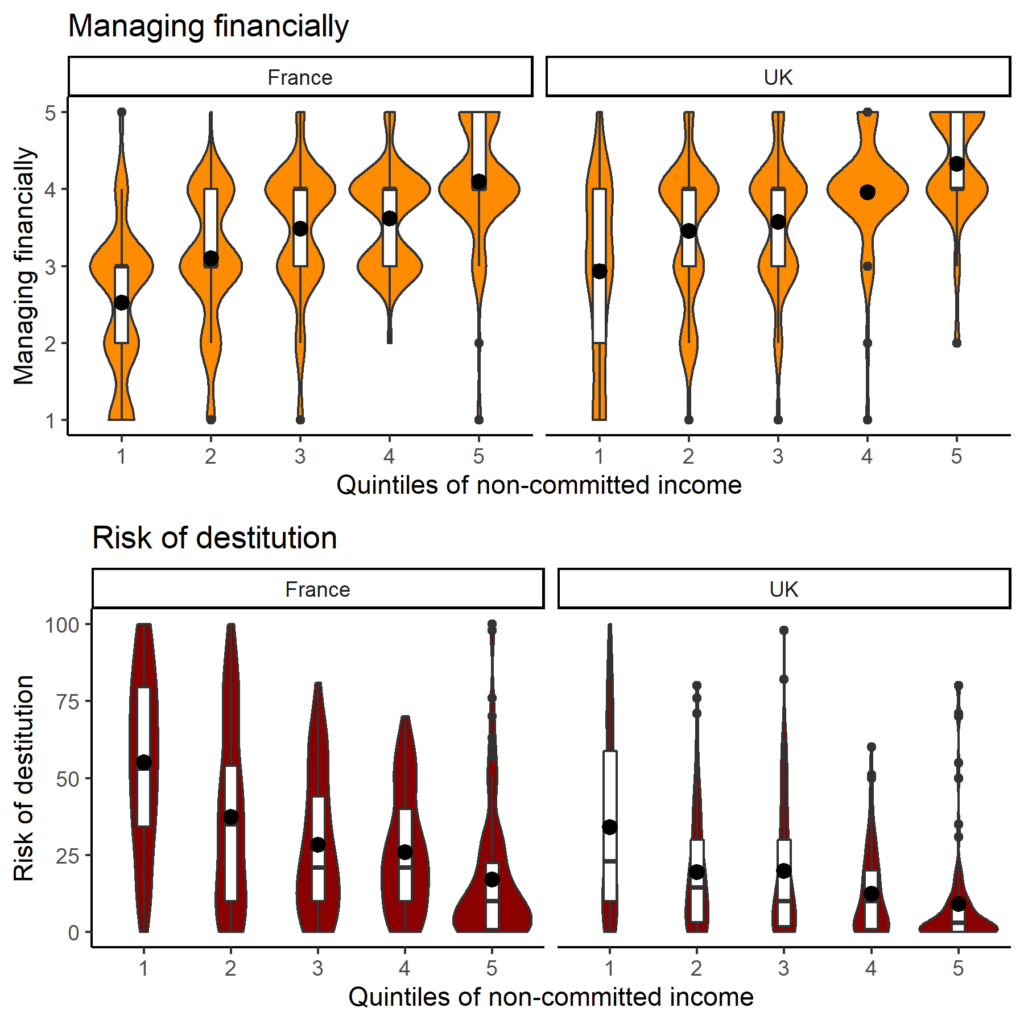

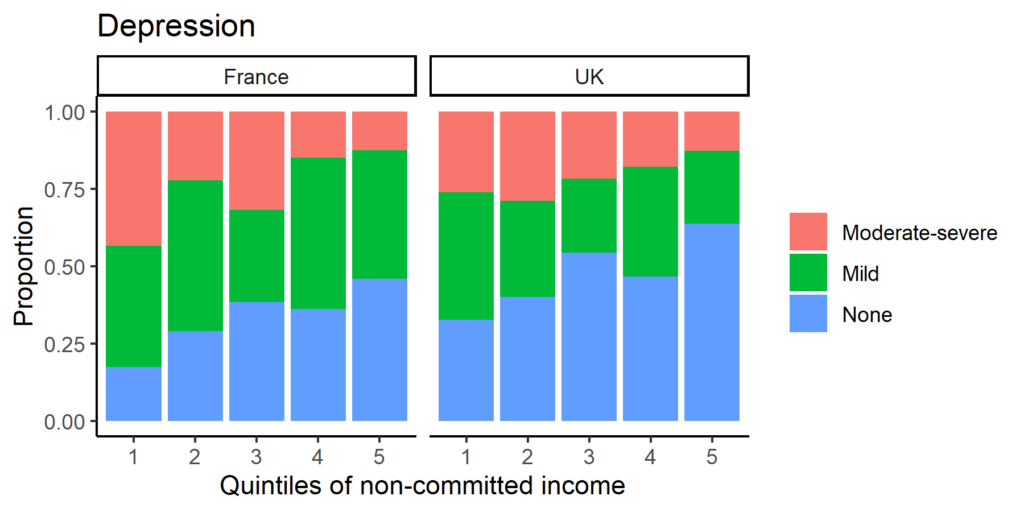

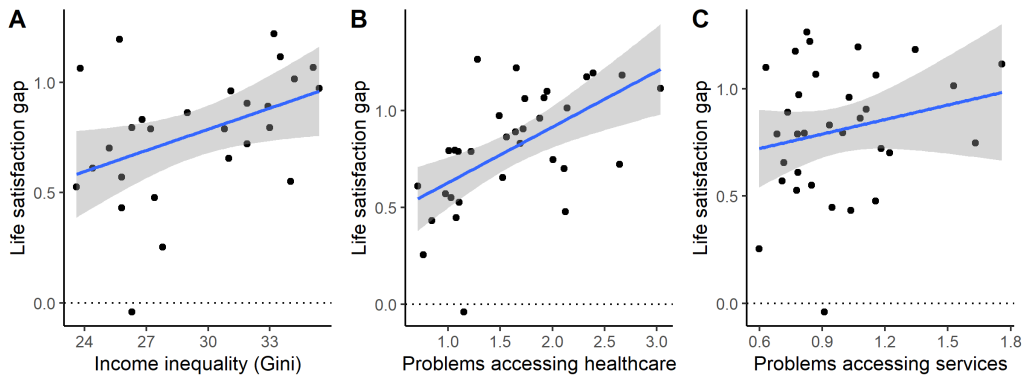

This position also opens the way for an appreciation of the subtleties of power in cultural dynamics. People’s willingness to acquiesce to cultural expectations will depend on such factors as their material resources, their power, their outside options, their alternative sources of social support. These are factors that change over time for different groups with the population, and are the standard fare of political science. Power is central to what persists. Powerful people will steer less powerful people into inferior outcomes, and they do not need to do this through overt coercion. They can achieve it through much subtler communication of expectations, and subtle diversions of the flow of incentives based on cultural conformity. On this view, humans are in almost all cases, somewhere in between B&A’s free-choosing inclusive fitness maximizer and their coerced person. They are trying to pursue their evolved goals, but always within a matrix of community expectations that they did not choose.<

Conclusion

Some years ago, I suggested that most social theories can be placed on a continuum from those that are too agentic (overemphasizing individual goal-directed agency) or too cultural (overemphasizing sociocultural and social-structural constraints) (Nettle, 2018). Much existing writing on culture and cultural evolution has gone too far in the cultural direction, thus losing contact with the strategic and goal-directed nature of human action. B&A is a valuable corrective in this regard. In this commentary, I have suggested that they might have gone a little too heroically in the agentic direction. We inhabit the middle ground, both structuring the social environment and being structured by it (Bourdieu, 1977; Giddens, 1984). However, as I have stressed, our quiescence, our willingness to be structured by social expectations in the surrounding community, is itself an outcome of past inclusive-fitness maximization in a highly interdependent, partner-choosing, social species.

References

Baumard, N., & André, J.-B. (2025). The ecological approach to culture. Evolution and Human Behavior 46(3), 106686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2025.106686

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice

Gächter, S., Molleman, L., &; Nosenzo, D. (2025). Why people follow rules. Nature Human Behaviour 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02196-4

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society. Outline of the Theory of Structuration.

Gintis, H. (2016). Individuality and Entanglement: The Moral and Material Bases of Social Life. Princeton University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1973). Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 1: Rules and Order. University of Chicago Press.

Keesing, R. M. (1974). Theories of Culture.Annual Review of Anthropology 3, 73–97.

Nettle, D. (2018). Hanging On To The Edges: Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life<. Open Book Publishers.

Nettle, D. &; Heintz, C. (2025). Studying culture from an evolutionary psychological perspective: approaches, achievements, and prospects. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/23pvr_v1

O’Connor, C. (2019). The Origins of Unfairness: Social Categories and Cultural Evolution. Oxford University Press.

Singh, M. (2022). Subjective selection and the evolution of complex culture. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 31(6), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21948

Theriault, J. E., Young, L., & Barrett, L. F. (2021). The sense of should: A biologically-based framework for modeling social pressure. Physics of Life Reviews 36, 100–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2020.01.004

The point of this post is to tell you a bit more about Act Now!, how it came about, and who its sinister-sounding author, the

The point of this post is to tell you a bit more about Act Now!, how it came about, and who its sinister-sounding author, the

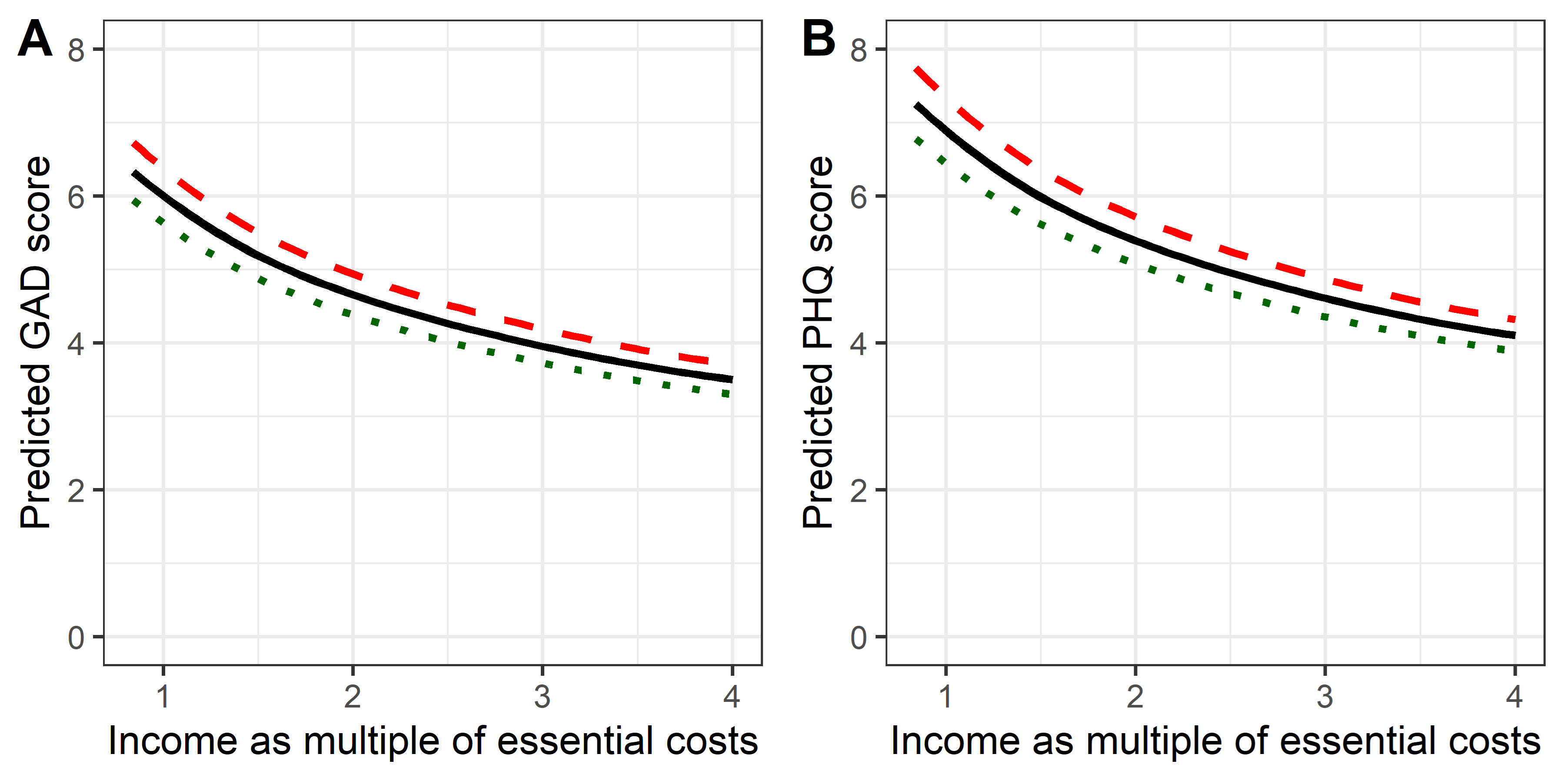

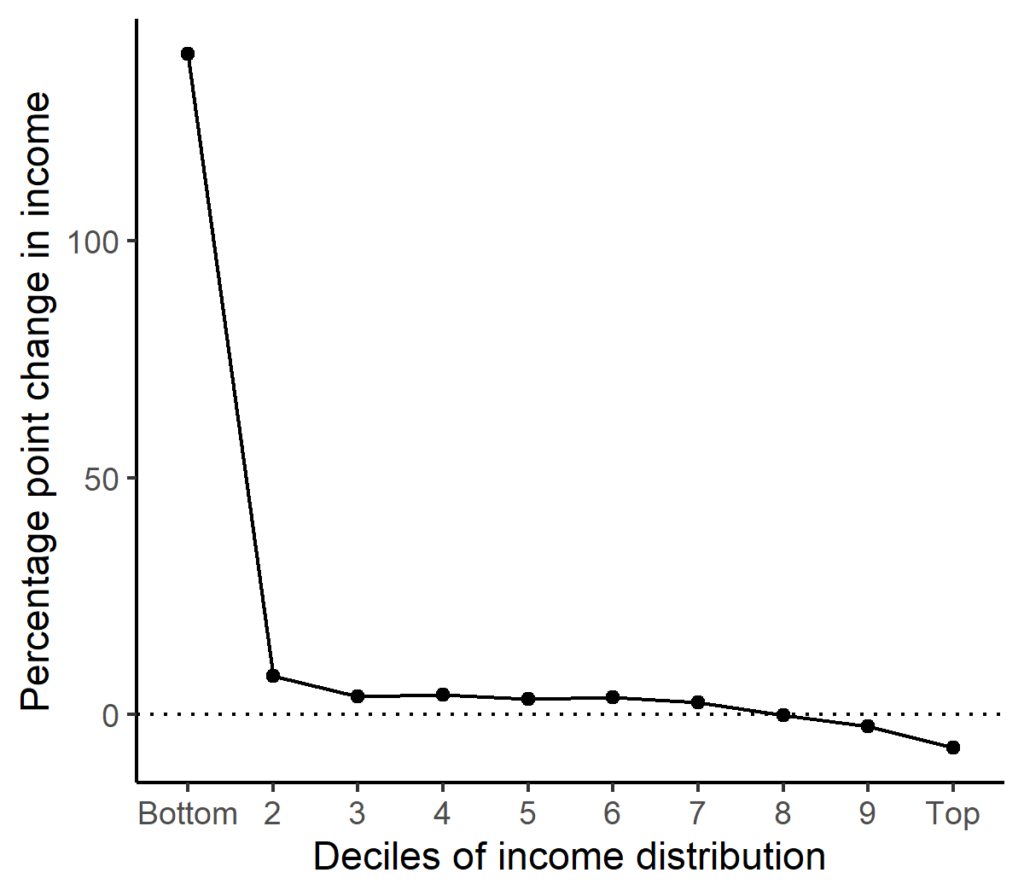

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

Many collaborators contributed to this study.

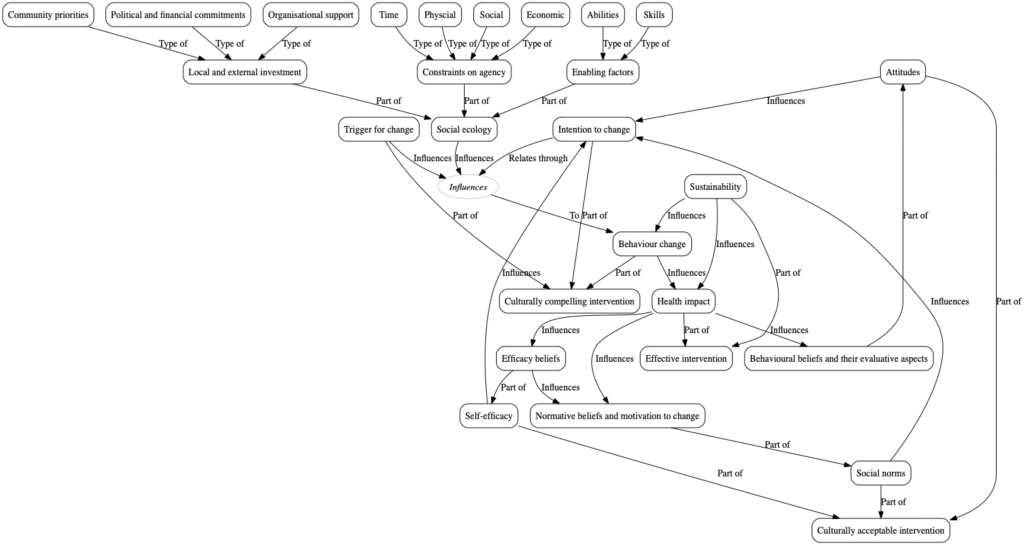

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

ew paper coming out in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

I am very excited about our imminent production of Matthew Warburton’s Hitting the Wall at Northern Stage on November 30th.

I am very excited about our imminent production of Matthew Warburton’s Hitting the Wall at Northern Stage on November 30th.